Living in Harmony with Earth

Perspectives

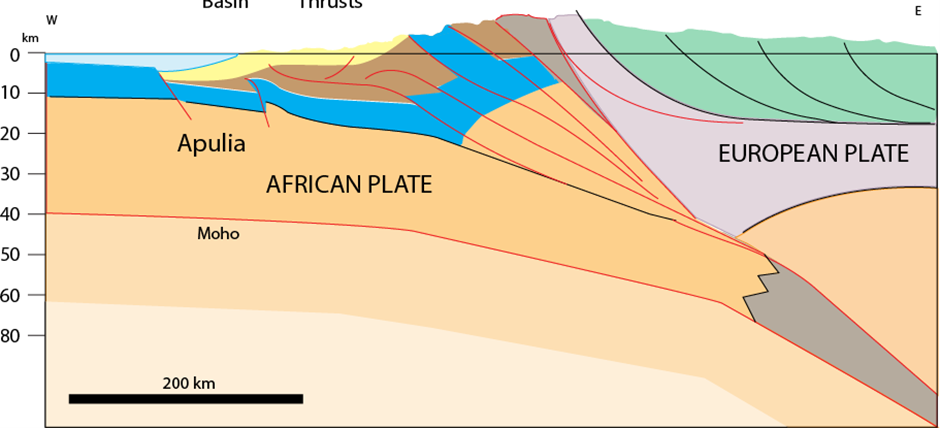

FORELAND FOLD AND THRUST BELTS

Foreland fold and thrust belts form part of orogenic belts which are regions of the Earth’s crust where two tectonic plates collide. Some of the world’s giant oil fields are located in such settings. In the past decades, however, foreland fold and thrust belts received little attention. But, improvements in exploration and recovery techniques, modernization of interpretation concepts, a better understanding of the hydrocarbon potential of such areas, and reopening of geographic regions previously inaccessible mean that foreland fold and thrust belts are opening up new opportunities for long-term investments and the prospect of superior returns to developers and related service providers.

The geological characteristics of foreland fold and thrust belts make them favourable places for hydrocarbons to accumulate. More than 700 billion barrels of oil equivalent (“BOE”) of known hydrocarbon reserves are estimated to occur in world’s foreland fold and thrust belts, of which c. 517 billion BOE in the Middle East with the remaining 183 billion BOE distributed across the world.

In the last decades, foreland fold and thrust belts have received little attention. Major and independent oil companies considered the development of hydrocarbon resources in onshore foreland fold and thrust belts as being challenging due to their rugged terrain, insufficient seismic data quality to allow unambiguous interpretation, difficulties in reservoir development due to uncertainties with respect to their structural evolution, and often unsuitable geopolitical environments. After many successes in the Middle East, Latin America, and Asia Pacific, major and independent oil companies left those areas for deep-water provinces that they considered less challenging.

Recent scientific advances give new insights into the opportunities for developing hydrocarbon resources in foreland fold and thrust belts. It is now feasible to invest in these regions for the following four key reasons:

1. Exploration and recovery techniques have been improving substantially over the past few decades. Seismic acquisition and processing techniques have improved significantly, computer modelling has become more powerful, and industry has learned a lot from similar structural styles offshore, in deep-water provinces where high quality 3D seismic imaging has allowed detailed analysis of structural development. New techniques for the integration of outcrop data with seismic, well, and reservoir production data led to significant changes in the way data is interpreted. Improvements in secondary recovery and EOR techniques have increased the efficiency of oil production from fractured carbonate reservoirs that are so widespread in foreland fold and thrust belts.

2. Interpretation concepts have been modernized. Understanding of structural geometries in foreland fold and thrust belts has evolved with both increasing data and the use of techniques that have allowed model development to move beyond traditional concepts. This evolution is influenced by the progressive incorporation of large amounts of data from wells drilled and seismic lines shot over producing fields. Historical reliance on a narrow suite of geometric models originally developed in the Rocky Mountains is also diminishing, reflecting expanding datasets in other foreland fold and thrust belts. Awareness of the limitations of such models have had important implications not just in recognizing new structural geometries but also in terms of magnitude and location of potential hydrocarbon resources that were previously overlooked.

3. Today we have a better understanding of the hydrocarbon potential of major foreland fold and thrust belts. Recent studies from the Zagros foreland fold and thrust belt indicate that some areas of the Zagros previously considered not to be prospective may in fact be prospective. Other recent studies on foreland fold and thrust belts in the rest of the world have suggested that the majority of them have very similar petroleum system elements (source rocks in Cretaceous-Tertiary oil prone marine shales, mudstone top seal, 40% mostly fractured carbonate reservoirs, and 40% sandstone reservoirs).

4. Geopolitical barriers to successful commercialization of thrust belt resources are falling. For several decades, major and independent oil companies have barely made new investments in large hydrocarbon-bearing regions in countries like Iraq and Iran. Recent successes in the Kurdistan region of the Zagros foreland fold and thrust belt are already having considerable implications for the development of hydrocarbon resources not just in these areas but elsewhere given the lessons that can be learned by working in these foreland fold and thrust belts.

Improvements in exploration and recovery techniques, modernization of interpretation concepts, a better understanding of their hydrocarbon potential, and reopening of geographic areas previously inaccessible mean that foreland fold and thrust belts cannot be perceived as prohibitive any longer. Investment in foreland fold and thrust belts would now provide the tools to reinvigorate the profitable development of very large oil and gas resources.